Window of Remembrance

© Stiftung Berliner Mauer

Have you noticed the “Window of Remembrance” yet? This site is dedicated to the people who died at the Berlin Wall. At least 140 people were killed at the Wall or died in connection with the East German border regime between 1961 and 1989. Most of them were refugees who were shot while trying to cross the border fortifications. Others died in an accident or took their own lives. But some people were shot or died in an accident who were not attempting to flee.

The Window of Remembrance presents photos of the people who died. Their names and birth and death dates are also shown. Each victim is remembered here individually. Relatives often place flowers or stones at the site or light a candle. A photograph could not be found for every victim. And a few niches were intentionally left empty in case more victims are discovered in the future.

The victims also include eight East German border soldiers who were on duty when they were killed by deserters, fellow comrades, a refugee, an escape helper or a West Berlin police officer. The photographs and names of these border soldiers are not included in the Window of Remembrance, however.

When the memorial was being created and the design of the Window of Remembrance was being planned, this issue was intensely discussed by the committees of the Berlin Wall Foundation. In the end, they decided not to include the border soldiers in the Window of Remembrance. It was argued that because they were helpers of the dictatorship – albeit often unwillingly as conscripts – they should not be honored alongside the victims of the dictatorship. The names of the eight border soldiers are presented separately on a column near the Window of Remembrance.

The first victim at the Berlin Wall

Many of the residents of the buildings located on the border made a spontaneous decision to flee. At first it was possible to leave through the front doors. But by August 18, these doors had been nailed shut or walled up. They were replaced by new doorways that led through back courtyards. In desperation, several residents jumped out of their windows or slid down ropes to escape to the West. West Berlin firemen on the sidewalk below held out rescue nets, trying to catch people and prevent them from being injured.

Ida Siekmann watched as the door to her building was barricaded shut on August 21, 1961. Early the next morning she threw her belongings out the window of her third-floor apartment. She jumped before the West Berlin firemen had a chance to catch her in their rescue net. Ida Siekmann was perhaps scared of being caught. She was badly injured when she hit the ground and died on the way to the nearby Lazarus Hospital – just one day before her 59th birthday.

The incident evoked a wave of outrage on the west side of the city. This was the first time someone had died at the Berlin Wall. Neighborhood residents and passersby were shocked. The press reported about it in detail. Following an official memorial service, a wreath was placed in front of the building at Bernauer Straße 48. It bore the inscription: “To the victim denied freedom.” A few days later a monument was erected at the site for Ida Siekmann.

Memorial sign for Ida Siekmann, ca. 1963 © Stiftung Berliner Mauer, Foto: Michael-Reiner Ernst

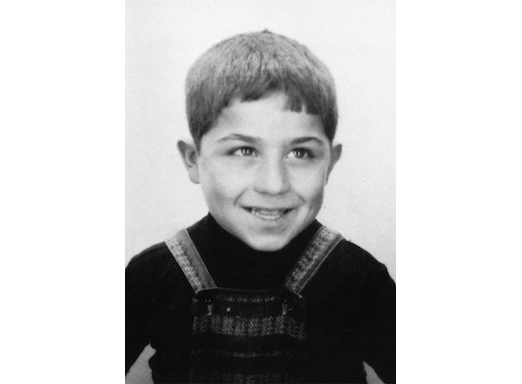

No help for an 8-year-old boy

His friend quickly notified a fisherman who sent the boy to get help from the nearby customs control post. The fisherman began to undress. But then he realized that this part of the Spree belonged to East Berlin. If he tried to rescue the boy, he would be putting his own life in danger. The East German border guards might mistake him for someone fleeing and shoot him. The fisherman decided not to jump in after the drowning boy. In the meantime the West Berlin police and the firemen had arrived at the Spree riverbank. They tried in vain to get a tanker and East German fire boat to rescue the child. A short time later a West Berlin police car arrived. The police began negotiating with an officer of the border troops who was posted on the Oberbaum Bridge about retrieving the drowned boy from the water. Two divers from the West Berlin fire department were getting ready. But they were refused permission to jump into the border waters.

Finally, after almost two hours, an East Berlin lifeboat arrived and a diver retrieved the child’s body from the water. That evening Cengaver Katranci’s mother was permitted to travel to East Berlin with two relatives. She had to identify her son at the Forensic Institute of the Charité Hospital. The body was transferred to West Berlin and was buried in Ankara on the request of the child’s mother.

The death of the eight-year-old boy led the Senate to announce that it would negotiate a treaty with East Germany over assistance measures should future accidents occur in the border waters. The terms were settled on in 1975. By then three more children had died in the Spree.

Portrait of Cengaver Katranci © Peter Rondholz

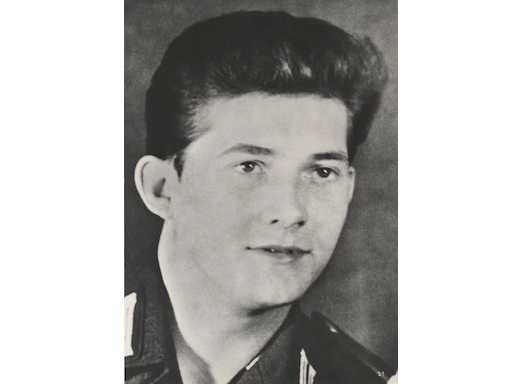

Shot and Killed on Duty

When guard leader Schmidtchen and his junior guard R. heard a noise, they did not make any connection to this warning. They left the former railway gatehouse and came upon two men in uniform. Schmidtchen had evidently assumed that the two men were on duty patrol. Guard R. later reported that he had approached them unsuspectingly and spoken to them. Then, suddenly, shots were fired. Later it was determined that the bullets had come from the weapon of the 19-year-old cadet Peter Böhme. Böhme had been planning to flee to West Berlin with his comrade, Wolfgang G. It is presumed that Jörgen Schmidtchen died immediately. Soldier R. returned fire and a shoot-out ensued during which Peter Böhme was also fatally wounded. Wolfgang G. however, remained uninjured and was able to make it safely to West Berlin. The next day he was quoted in the press as saying: “It was horrible. But we had no other choice. It was us or them.”

In his investigation report the commander of the 2nd border brigade to which Schmidtchen had belonged concluded that Schmidtchen had acted imprudently. But not a single critical word was spoken publicly about him by the military leadership. He was posthumously promoted to sergeant and his parents received a one-time payment of 500 marks. East Germany even had streets and schools named after Jörgen Schmidtchen.

Jörgen Schmidtchen was the first border policeman to die while on duty at the border with West Berlin after the Wall was built. His fate illustrates how the military border regime established at the Berlin Wall by the East German leadership also bred counter-violence. In individual cases, refugees, military deserters and escape helpers used weapons against border guards to secure passage to West Berlin. This led to the death and injury of members of the armed units guarding the border fortifications in and around Berlin. A total of eight East German border soldiers were killed while on duty at the Berlin Wall.

Porträt Jörgen Schmidtchens © Polizeihistorische Sammlung Berlin